Here’s a crisp, two-language unpacking.

English

What the pun does

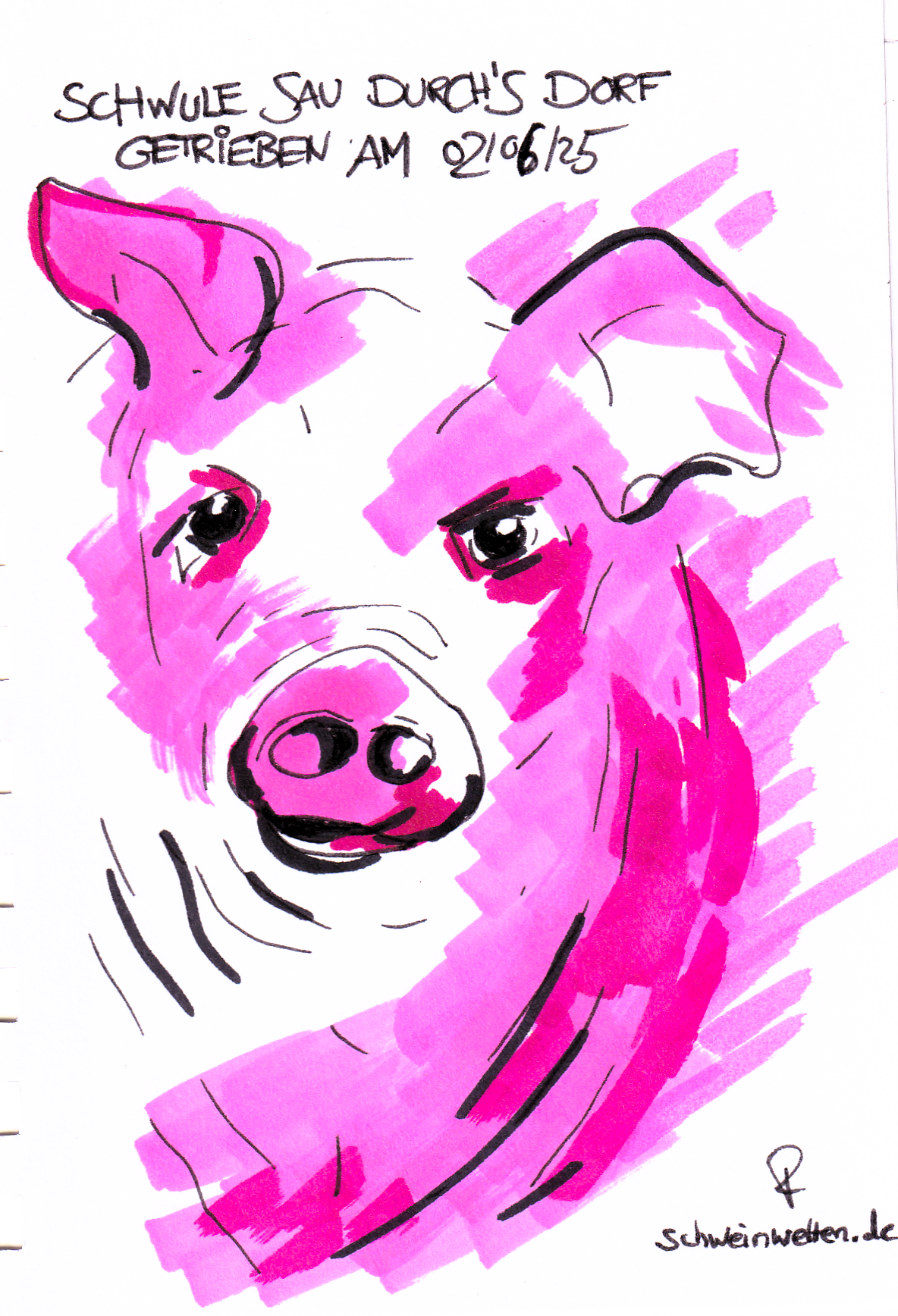

- Triple split:SchWeinWelten can be read as

- Schwein-welten → “pig worlds,”

- Sch + Wein + Welten → “wine worlds” hidden inside Schwein,

- Schwein + Welten → “worlds of swine.”

The deliberately odd camel case (a German Binnenmajuskel) spotlights Wein inside Schwein, turning one compound into a visual collage.

- Semantic friction: It fuses butchery (pigs, flesh, trade, everyday labor) with festivity and fermentation (wine). That tension—abattoir vs. banquet, matter vs. myth—creates a small “world-making” device in the word itself.

- Cultural echoes: In German idiom Schwein haben = “to be lucky”; in popular culture pigs oscillate between the abject and the auspicious. Welten (worlds) scales this up from animals to cosmology, satire, and social order.

- Dada logic: Calling it made “according to the non-existent principles of Dadaism” is a witty meta-move. Dada favored anti-programs, chance juxtapositions, nonsense, and typographic play. Your family background (“son of a butcher”) grounds the nonsense in lived material culture—classic Dada: everyday stuff cut up, shuffled, re-signified.

- Bonus bilingual quirk: In English, s/wine—swine literally contains wine. The pun survives the translation in a sly letterplay.

Good English renderings

“SchWeinWorlds” (lets the German stem show through, more avant-garde)

“PigWorlds” (keeps the core sense)

“sWineWorlds” (mirrors the inner wine)

Leave a Reply